I came across this paper relating the issue of women in ministry to trinitarian theology. I find this review of Grenz's work quite helpful. I appreciate the starting point of theo-ontology as opposed to contemporary socio-cultural currents and constructs for framing a theology of gender as it relates to church ministry. (i.e. political correctness...is that a theological source?)

As other articles in this journal make clear, Stanley Grenz was a careful and articulate theologian who produced some of the most deeply engaged evangelical theology of the last decade. Should this be Grenz’s only legacy, it would be impressive. But Grenz was more than simply an academic theologian. Indeed, Grenz was concerned with contributing to the whole community of God, as the title of his systematic theology makes clear.(1) This included not only writing academic theology, but also writing on more concrete issues and challenges that confront the church. The diverse subjects covered in his substantial body of books range from a primer on Baptist congregations to a ministerial response to AIDS. Among the concerns with which he was seriously engaged was the affirmation of women’s roles in ministry, particularly within the evangelical context in which he functioned. This essay will survey the contributions of Grenz and others like him in this area, and it will reflect on how these contributions might be fruitfully received, not only by the specifically evangelical audience to which they were targeted, but also by the more general community of the mainline church.

As a recently released book shows, evangelicals have historically been very open to the participation of women in various levels of ministry.(2) Especially in the decades surrounding the turn of the 20th century, examples of women actively preaching and teaching in evangelical settings and denominations abound. Indeed, this participation was not without theological reflection; both females and males wrote books that biblically justified women’s ministry. Most of these works tended to take one of two stances. Either they argued that the Joel 2 prophecy about daughters prophesying was fulfilled in Acts 2, thereby justifying women’s preaching, or, more radically at the time, they argued for total equality based on the broader theological theme of creation and redemption, in which the negative effects of the fall were redeemed by Christ’s atoning sacrifice.(3) Also, among the holiness movements, pneumatological defenses which emphasized the spirit's calling to Christian ministry were especially prevalent.

This tradition began to decline in the 1930s and was soon virtually eliminated due to the rise of separatist fundamentalism and its more literalist scriptural hermeneutic.(4) It was not until the 1970s that evangelicals began to challenge the nearly universal evangelical assumption that women should be barred from ministry.(5) The first prominent evangelical book in this vein, All We’re Meant to Be,(6) appeared in 1974. This was quickly followed in 1975 by Paul Jewett’s controversial Man as Male and Female(7) and then by Patricia Gundry’s 1977 Women Be Free!(8) Following Gundry, a slow but steady stream of books were published in the 1980s, often arguing on scriptural and exegetical grounds for women’s participation in ministry. Some of the books approached the issue from different perspectives, like Janette Hassey's 1986 book No Time for Silence,(9) which presented the turn-of-the-century movement mentioned above as an argument that evangelical feminism was not “a misguided effort to emulate the secular feminism which [had] gained ground since the 1950s.”(10)

Grenz stepped into this mix when, in 1995, Women in the Church: A Biblical Theology of Women in Ministry,(11) co-written with Denise Muir Kjesbo, was published. Women in the Church argues that “historical, biblical and theological considerations converge not only to allow but indeed to insist that women serve as full partners with men in all dimensions of the church’s life and ministry.”(12) The book is “by evangelicals” and “is also primarily for evangelicals.”(13) After 1995, Grenz made a concerted effort to keep the topic of women’s participation in ministry on the evangelical agenda. In the same year, an article rehearsing many of the theological arguments from Women in the Church appeared in the Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society.(14) In 1998, the same journal published another article, which, while on a slightly different topic, continued to argue in a similar vein.(15) While Women in the Church did address specific biblical texts, Grenz argued that the discussion needed to “move beyond isolated passages of Scripture to speak about broader theological themes”; he emphasized that it is “ultimately in the context of foundational doctrinal commitments that the biblical texts find their cohesion.”(16) Grenz is noteworthy in that his academic articles consistently moved to these foundational doctrinal commitments. His theological arguments for the full participation of women in ministry were consistently rooted in the doctrine of the Trinity.

In rooting his discussion here, Grenz joined a significant discussion among evangelicals concerning the doctrine of the Trinity and its implications for human interaction. As early as 1979, before the egalitarian movement had gained much momentum, Wayne Grudem, a prominent evangelical voice in this discussion, stated that “a proper understanding of the doctrine of the Trinity may well turn out to be the most decisive factor in finally deciding” the debate over male-female relationships.(17)

The question significant to this issue that arises from the doctrine of the Trinity concerns the relationship of the Son to the Father. Specifically, is the Son eternally subordinate to the Father? If so, or if not, what are the implications for the traditional subordination of females to males? Evangelicals have offered different answers to these questions. For instance, some argue that the Son is eternally subordinate to the Father and that females are called to model this subordination in their relationships to males.(18) Such authors are quick to state that they do not think this subordination renders the Son less than God – there is subordination with respect to roles and equality with respect to being.(19) This idea has provoked significant response, including a full-length book by Anglican priest Kevin Giles who argues against eternal subordination with the question of gender relationships in mind.(20)

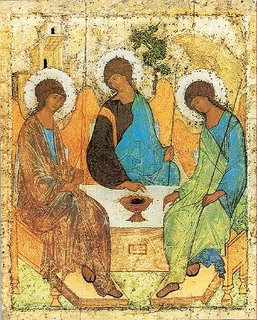

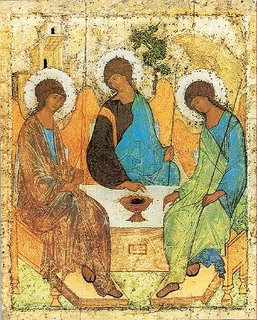

Grenz is well known for his work on the Trinity, and the way he relates the Trinity to human relationships is also important. Grenz advocated a “social Trinity,”(21) which he argued should be a model for a humanity created in the imago Dei. This image “is found in human community”(22) and should be reflected in individual male-female relationships. Furthermore, it should be reflected in the church. While Grenz did not reject the idea that “the Son is in some sense subordinate to the Father within the eternal Trinity,”(23) he emphasized that “the Father is also dependent on the Son.”(24) This balance “leads to an emphasis on mutual dependence and the interdependency of male and female in human relationships,”(25) which therefore calls for “structures that foster the cooperation of women and men in all dimensions of church life.”(26) In this way, Grenz struck a compromise between the two common stances.

In addressing women’s roles in ministry, Grenz and his interlocutors have taken up a very significant debate. On the one hand, it is important in its practical applications. Especially within the evangelical church, a large percentage of which does not permit women to hold authority over men, it is imperative that this topic continues to be addressed. It should also be noted that evangelical groups are not the only ones struggling with this question. Significant mainline bodies are still addressing it to some extent; for instance the Church of England recently debated opening the way for female bishops. For example, the Church of England recently debated opening the way for female bishops. For this body, the question of women’s ministry also impacts the larger Anglican Communion, which has recently been threatened with schism from various sides, including traditionalists who would refuse the oversight of a female bishop.

What is even more important than these concerns, however, is the ground on which this issue is being addressed. While the discussion was originally focused on specific biblical texts, it has increasingly shifted to theology, and it has narrowed in on one of the doctrines most crucial to Christianity: the Trinity. In addressing important issues in church life by looking first to scripture and then to how it should be read theologically, Grenz and evangelicals like him have provided an admirable example for other groups to follow. Not only have they been willing to wrestle with one of the most significant Christian doctrines in an attempt to better understand the God whom we worship; they believe such wrestling matters to the life of the church. It can only be hoped that other groups might be so brave.

David Komline is an M.Div. junior at Princeton Theological Seminary.

Notes

1 Theology for the Community of God (Nashville: Broadman & Holman, 1994).

2 Ronald W. Pierce and Rebecca Merrill Groothuis, eds., Discovering Biblical Equality: Complementarity without Hierarchy (Downers Grove: IVP, 2004). See especially the chapter entitled “Evangelical Women in Ministry a Century Ago: The 19th and Early 20th Centuries.”

3 Pierce and Groothuis, eds., Discovering Biblical Equality, 45.

4 Ibid., 52.

5 For more information on this and the movement since then, see the chapter “Contemporary Evangelicals for Gender Equality,” in Pierce and Groothuis, eds., Discovering Biblical Equality.

6 Letha Scanzoni and Nancy Hardesty, All We’re Meant to Be: A Biblical Approach to Women’s Liberation (Waco, TX: Word, 1974).

7 Paul K. Jewett, Man as Male and Female: A Study in Sexual Relationships from a Theological Point of View (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1975).

8 Patricia Gundry, Woman, Be Free! (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1977).

9 Janette Hassey, No Time for Silence: Evangelical Women in Public Ministry Around the Turn of the Century (Grand Rapids: Academie Books, 1986).

10 Roger Nicole’s endorsement on the back cover of Hassey, No Time for Silence, quoted in Pierce and Groothuis, eds., Discovering Biblical Equality, 64.

11 Stanley J. Grenz and Denise Muir Kjesbo, Women in the Church: A Biblical Theology of Women in the Ministry (Downers Grove: IVP, 1995).

12 Grenz and Kjesbo, Women in the Church, 16.

13 Ibid., 17.

14 Stanley Grenz, “Anticipating God’s New Community: Theological Foundations for Women in Ministry,” Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 38 (1995): 595-611.

15 Stanley Grenz, “Theological Foundations for Male-Female Relationships,” Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 41 (1998): 615-30.

16 Grenz and Kjesbo, Women in the Church, 142.

17 Wayne Grudem, “Review of George W. Knight, The New Testament Teaching on the Role Relationship of Men and Women,” Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 22 (1979): 376.

18 E.g., Wayne Grudem, Evangelical Feminism and Biblical Truth (Sisters, OR: Multnomah, 2004): 405-42, which is an extended argument for this position.

19 Grudem, Evangelical Feminism and Biblical Truth, 415.

20 Kevin Giles, The Trinity and Subordinationism: The Doctrine of God and the Contemporary Gender Debate,(Downers Grove: IVP, 2002).

21 Grenz, “Theological Foundations,” 617.

22 Grenz, “Theological Foundations,” 620.

23 Grenz, “Anticipating God’s New Community,” 597.

24 Ibid.

25 Grenz, “Anticipating God’s New Community,” 598.

26 Ibid.