God's transcendent providence

Is God truly in control of human history? People living at the beginning of the twenty-first century might well have their doubts. Theologians, pastors and laypeople continue to ponder, and at times struggle mightily with, the question of God's goodness and power as manifested in the midst of the unprecedented suffering and evil of our century. Modern horrors such as the Holocaust, the violence in Darfur, the death of millions in Cambodia, Rwanda and Kosovo, and the more recent destruction of the World Trade Center towers silence any flippant responses to the question of God's control and governance of human history.

Is God truly in control of human history? People living at the beginning of the twenty-first century might well have their doubts. Theologians, pastors and laypeople continue to ponder, and at times struggle mightily with, the question of God's goodness and power as manifested in the midst of the unprecedented suffering and evil of our century. Modern horrors such as the Holocaust, the violence in Darfur, the death of millions in Cambodia, Rwanda and Kosovo, and the more recent destruction of the World Trade Center towers silence any flippant responses to the question of God's control and governance of human history.Each of us has at one time or another asked the question why. Whether we have encountered or experienced an accident, sickness, natural disaster or war with its accompanying horrors, the question wells up within us--Why? Why didn't God protect us? Why couldn't circumstances or timing have been different?

excerpt from Learning Theology with the Church Fathers, (Hall, 2002)

I have been learning theology with the church fathers. I have been impressed with a number of things in my reading. In his treatise on the providence of God, Chrysostom continually exhorts his readers to learn to think and live like a Christian. The one who has learned to think like a Christian, the one whose thinking has been shaped by the gospel and the realities it represents, will not judge God's providence by appearences. Instead, genuine believers will remain sensible and vigilant, wary of making a premature judgment concerning God's actions or permission. They will understand that the events of this life in themselves are indifferent matters and take on the character of good or evil according to our response to them.

By way of contrast, those who are "worldly, difficult to lead, self-willed, and utterly carnal" will continually misread God's providence because they lack the eyes to see him at work, a vision that only comes to those who are actively exercising faith, that is, allowing their perspective to be shaped by the gospel and acting accordingly.

The believer who possesses a deeply grounded Christian disposition will experience pain and grief on his journey home, but never harm." (Hall, p. 170)

It's the age old question: "Where is God when it hurts?"

The other great idea taken from the chapter entitled, "Christ Divine and Human," is how the church fathers developed a theological framework to "explain" this ineffable mystery. Much of the controversy in the historical era is reflected in the exchanges between Bishop Cyril of Alexandria and Nestorius. Basicly Nestorius watered down the incarnation by thinking of it in terms of God exalting the human, Christ, through an indwelling association. But it was not God taking on flesh in the fullest sense.

Cyril finds fault with the methodology of Nestorius. As far as Cyril is concerned, Nestorius is fundamentally a theological innovator. Cyril is convinced that Nestorius has ignored the previous theological reflections of the church in the construction of his theological proposal regarding the relationship of Christ's deity and humanity. Cyril argues, "he innovates as seems fit to him."

Hmmm. I ponder the implications of the methodology one uses in interpreting Scripture. How one views the Apostolic Tradition will impact the way in which we approach the Scriptures and interpret it. As Mennonites, how is theological innovation a part of our tradition as we read and interpret the Scriptures?

The early church fathers would tell us that the reality of the incarnation simply refuses to fit within an entirely coherent logical framework. Cyril would encourage us to think concurrently, holding seemingly contradictory thoughts side by side and allowing the tension between them to remain rather than attempting to resolve the tension through a premature rationalistic maneuver.

In the twentieth century Robert Oppenheimer advocated much the same methodology, but for use in a different discipline, contemporary physics. Why is there a need for occasionally logical inconsistency? Huston Smith notes the presence of "many findings in contemporary physics that refuse to be correlated in a single logical framework." Hence, Oppenheimer's proposal that physicists employ a "Law of Complementarity as the basic working concept in the field, meaning by this (in part) that opposing facts must be held in tension even when logically they are at odds if they can help account for phenomena observed. In more than one field, it seems, reality can be more subtle than man's logic at any given moment." (Hall, p. 96)

I find this analogy very helpful. This model allows for us to acknowledge the mystery of our faith that does not fit nice and neat into the containers, and the narratives of Enlightenment rationalism. It also strikes me as possible language to describe how it is possible to say that the Body of Christ is manifested on earth in one, holy, catholic and apostolic Church despite the messy, confusing evidence that would seem to counter this confession.

On Tuesday I begin the course Conversations with Anabaptist Theology Today, taught by Brinton Rutherford. I am looking forward to exploring these questions and many others during this course.

I was thinking about the challenge of raising children in a time of war. This post is already very long so I will save this for another time.

Peace

4 Comments:

At 3:02 PM , Anonymous said...

Anonymous said...

I have never thought about how our interpretation of the incarnation really does affect our theology on human suffering. I wonder if it is the influence of Nestorius' views which help perpetuate a prosperity gospel.

The other night I heard a sermon on how God wants us to prosper. Despite qualifiers stating he thinks there are errors in a prosperity gospel, he went on to say that he believes that Christians who obey, have faith and listen to the Word of God will prosper. I heard not one word qualifying his statements for those Christians who do suffer in this life. In fact, he said that "do you really think that God will let you lose your family or your car (or maybe he said home)?" His basic premise being that (my interpretation) if we make ourselves super-human, we will succeed, for that is what God wills. My first response was, "this is a very American sermon!" What about all the Christians living in Afghanistan, Iraq, Kosovo, etc. who suffer, even now in poverty, war, losing loved ones, from rape, etc. Have they, by virtue of where they live, received God's judgment for disobedience or lack of faith?

But perhaps this notion of God "exhalting the human, Jesus" makes people think that somehow it is possible for us too. If we are super-spiritual enough or victorious in our spiritual life, we can live above suffering. Is this what the idea means? Is this really what is expected of all of us????

So, if I do not buy into the exhalted incarnation, how to I teach, model or explain that suffering is going to be part of Christian life when I also say I trust in an almighty God? Yes, the gospel does look foolish when you consider the Incarnation who chose to stoop down to take on suffering.

At 5:02 PM , Brian Miller said...

Brian Miller said...

Thanks for your response dml. I agree that our theology of the incarnation, Jesus' death and resurrection will have a huge impact on our understandings of the Christian life, salvation, and what it means to follow Jesus.

In the chapter on God's providence, there is also a very helpful reference made to Chrysostom's theology of death.

Death, surely, is a genuine evil, yet Chrysostom argues that death can be a benefit for both the believer who has died and for those who remain behind. How so? Those who continue to live in this world after the death of a loved one have received a powerful lesson on the transitoriness of life and the danger of thinking and acting as though life will never end. One is "humbled, learns to act in a more level-headed fashion, is taught to think in a more spiritual manner, and introduces into his mind the mother of all goods, humility.

If we judge solely according to appearances, we will view death only as an evil. Hence, Chrysostom insists, the danger of an inexperienced and foolish person "immediately expressing at the outset a premature opinion." If we analyze death in the wider light of the gospel, though, Chrysostom believes it can be seen as a genuine good.

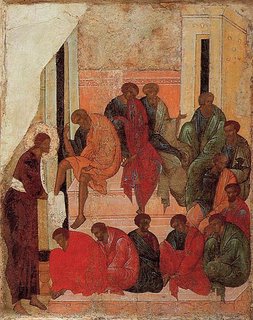

Chrysostom also enjoys illustrating the goodness of providence and the dangers of the passions from the story of Joseph. Joseph represents for Chrysostom the genuine Christian who bridles one's passions, refuses to judge by appearances and waits for the final outcome of events before passing judgment on God's providence.

Chrysostom emphasizes that Joseph's ability to respond wisely to God's providence and his own suffering was framed by a specific interpretive stance before God and his providential acts. That is to say, how Joseph chose to respond in his circumstances was molded significantly by his willingness to shape his judgment of affairs within certain specific guidelines. These hermeneutical boundaries--the nature of God's character, the inherent incomprehensibility of his providence and the guarantee of final deliverance in the future--enabled Joseph to respond faithfully to God's providential ordering of his life.

At 3:57 PM , Anonymous said...

Anonymous said...

You say it is the age old question, "where is God when it hurts?" But what I hear you really asking is, "can we trust that God's providence exists when it hurts?"

Furthermore, I struggle with the words "genuine Christian" as they are used in your post. Yes, I understand:

"The one who has learned to think like a Christian, the one whose thinking has been shaped by the gospel and the realities it represents, will not judge God's providence by appearences. Instead, genuine believers will remain sensible and vigilant, wary of making a premature judgment concerning God's actions or permission. They will understand that the events of this life in themselves are indifferent matters and take on the character of good or evil according to our response to them."

I struggle with saying "genuine believers." When we see people I would call genuine believers struggling with pain and suffering, how can we judge them when they are still at the point of questioning God's providence? The very fact that we are human means that we will struggle with anger, pain, bitterness, etc. Yes, we should exhort one another to trust God's providence, but I think we also need to be careful not to use our trust and understanding of it to provide pat answers to life's difficult questions. When theology comes down to practice/application, I would rather start with the fact that Jesus does understand our suffering and weeps with us in our pain. I do believe that, at some point, genuine Christians should come to accept/acknowledge God's providence. Obviously, like Joseph, that acknowledgment is a sign of our faith. And I do believe that the testing of our faith produces endurance. But for some, it takes a lot longer than others. I don't feel comfortable with the language which judges or implies that those who struggle with trusting God's providence are less than genuine Christians.

At 4:33 PM , Brian Miller said...

Brian Miller said...

dml,

Thanks again for sharing your response. Just one clarification. It sounds like you are framing your response in a way that attributes the comments on being a "genuine Christian" to me. These two posts on God's providence are all drawn from my reading about Chrysostom. Your response still is valid, it just is taking issue with Chrysostoms language ("genuine Christian"}, not mine.

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home